.

With the current financial and structural upheavals across UK civil society, organisations have to be highly adaptable in order to survive. They need the capacity to develop brilliant innovations, and they have to implement these quickly and sustainably. Many organisations have the raw talent for innovation but find it tough to embed new ideas in the system. This is my framework for harnessing that talent and giving it shape – making the most of tightly stretched resources, and investing your energy where it is most effective.

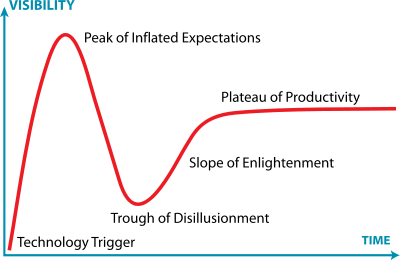

I am very excited by The Gartner Hype Cycle. It is an unlikely source of inspiration for me because it’s actually a tool for assessing the maturity of new technology innovations! But I think it can also be applied to the way we understand how cultural change is driven – whether this is internal organisational innovation or wider social policy change. I’m really interested to hear what you think of this.

.

Firstly, to explain the Hype Cycle in its original context as it applies to technology:

- A new technical discovery creates buzz – a Technology Trigger.

- It is hyped in the media to a Peak of Inflated Expectations – suggesting exciting possibilities that seem to take us into the realm of science fiction. (eg. currently it’s cloud computing that’s getting hyped.)

- But then this new technology doesn’t live up to its elevated expectations, and instead a Trough of Disillusionment sets in. (eg. consumer-generated media seems to be going nowhere at the moment.)

- Then a second wave of interest and enthusiasm adopts this technology and accelerates its development – there is a stable and evolving Slope of Enlightenment. (eg. app stores are becoming widely appreciated.)

- A third wave then improves reliability and user experience, and it is accepted in everyday practice. It reaches a Plateau of Productivity. (eg. speech recognition software is now commonplace.)

I came across the Hype Cycle via my favourite new technology blogger, Digital Tonto, who makes 3 essential observations about the process of developing innovations:

- Technology doesn’t exist in a vacuum but must interact with other ideas to become useful. “It’s when ideas and technologies combine that real value is unlocked.” (My interpretation is that technological innovation needs to fit with the social context to become a social innovation.)

- Innovation requires two profoundly different skill-sets to take hold: one to create radical new ideas; and another to bring about mass adoption of these ideas.

- It’s very difficult for these two strands of innovation to co-exist – the strands need to be separate to allow both to flourish, but must be sufficiently networked to enable synergies to happen between them.

Of course there are lots of practical differences between taking new technology to market, and driving cultural change, but I think the overall trends from the Hype Cycle are relevant to our thinking about change, and Digital Tonto’s essential points about technology are transportable to the cultural change process too.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

This is my take on The Gartner Hype Cycle from an organisational perspective:

- Leaders will identify a Trigger for radical change.

- They will work with their top teams to build their vision of a ‘brave new world’ for the organisation – then announce it to the staff with a great deal of enthusiasm. This risks being a Peak of Inflated Expectations if the anticipated change is too idealistic and unrealistic about what the organisation can handle. Staff experience it as hype.

- A few staff may ‘get it’ right away, but on the most part the proposed innovation will fail to register with the workforce. People lower down the hierarchy will struggle to engage with the idea or to appreciate its practical implications for their work. They will be reluctant to let go of ‘the way we do things round here’. The proposed changes will fall flat and run adrift in the Trough of Disillusionment.

- Then leaders will invest a great deal of effort, pressure, engagement and persuasion to get the rest of the organisation to grasp the value of the idea. They will involve staff in more solid, practical analysis – developing a business plan, and testing the viability, applicability, risks and benefits of the proposal. Gradually staff will take ownership of it, and fit it to their way of working – it will travel up the Slope of Enlightenment as they improve its ‘usability’ and ‘debug’ working practices.

- The benefits of the new ways of working will be demonstrated and accepted as routine practice, and the idea will reach the Plateau of Productivity.

What I would add about the Hype Cycle as it applies to cultural change, is that the process of adopting an innovative idea and assimilating it into everyday practice dilutes its original radical edge. On the one hand this reflects the success of the change programme – something new has been accepted and no longer poses a threat to staff. On the other hand it also reflects the fact that established culture ‘neutralises’ the impact of change – making it more mundane and less profound than the leader might have expected. It doesn’t conquer the peak of inflated expectations, but instead settles somewhere lower down the slopes!

In my consulting I come across pioneer leaders who feel gutted at this point when their radical change programmes don’t yield the rush of exhilaration and success that they had hoped for. Some want to move on to a different organisation to have a go at changing another system. Others want to plunge into a new change venture in the same organisation. Either way if they don’t first take stock of their mental models of change, they risk frustrating themselves unnecessarily all over again.

I think it’s essential for leaders to recalibrate their expectations and to refocus their energy where it is most effective. They need to recognise that something will inevitably be ‘lost in translation’ between original concept and working practice, and therefore that they need to work hard at connecting up the different parts of the Cycle to minimise this effect. It takes sophisticated integration to achieve sustainable change – rather than heroic solo efforts to scale the peak of inflated expectations. Leadership is about chemistry, and finding the right fit with the organisation.

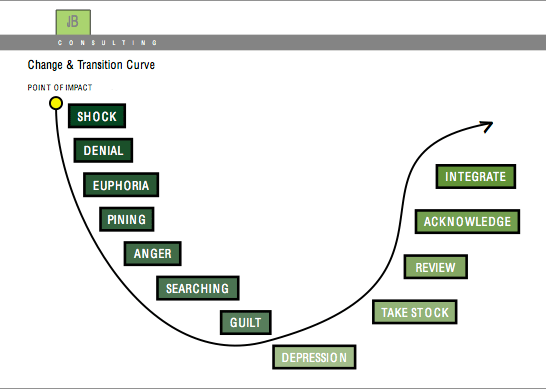

You may have noticed that The Gartner Hype Cycle is similar to the Change Curve that I described in my earlier blog on How To Handle Those Really Tough Decisions In Your Organisation . While the Hype Cycle describes the mental process involved in adopting new ideas, the Change Curve describes the psychological adjustments involved in adapting to difficult changes. If you put both models together, you can identify the most appropriate strategies for supporting your staff and keeping them engaged through the different stages of organisational change.

Here’s a checklist for staying focused and making your interventions more effective:

- For change to be compelling it has to resonate with meaning for the people you want to engage, so make sure that your innovation fits the organisational context.

- Anticipate peaks and troughs in the change process so that they don’t throw you off course. When these occur, hold the organisation steady and provide containment for your staff’s anxieties.

- Help your organisation to anticipate these peaks and troughs too by talking about them at the start of the process when everyone is most in alignment. Explain that differences will become more apparent, and that these may be painful and uncomfortable at times, but that the organisation will be better for the change, and you will all survive the experience.

- If you find your ideas falling on stony ground, resist the urge to push harder at ‘hyping’ them. Step back and think about what mechanism will bridge the gap between your proposed innovations and the practical realities of those who have to implement these for you.

- Develop the talent in your middle management teams to provide a ‘translation service’ between senior leaders and those at the coalface.

- Encourage frontline teams to experiment with implementing your ideas – to transform these ideas into practical processes with coalface ‘usability’.

- Encourage service users to demand more so they create a ‘pull’ to reinforce the changes that you are pushing.

- If you want to introduce profound change, it is better to approach it as a series of initiatives – to use the cumulative effect of several waves of change so that their momentum isn’t neutralised.

- Empower your staff to be the instigators of change, rather than just the implementers of top-down initiatives. Create separate space for the organisation to focus on generative ideas, free of the pressure to justify how those ideas will be implemented. Engender a buzz of excitement and expectation that innovation will happen.

.

This blog describes the implications of the Hype Cycle for internal organisational change. In my next blog I will pick up on the very different implications for wider social policy changes. I believe it identifies significant opportunities for civil society organisations to put themselves on the map and take advantage of the disillusionment that arises in the early days after new government policies have been hyped.

I’ve already had some great conversations about these ideas, so I hope they resonate with you too. Do please leave comments or contact me directly let me know your responses to this article.

.

.

My grateful thanks to Dr Barbara Grey, Director of Slam Partners, South London & Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust, for contributing additional ideas to this post.

.